Restoring Democracy - A Thought Experiment

Democracies: an Endangered Species?

In recent years, democratic governments have had their fair share of troubles. The US presidential election of 2016 was probably one of the most shameful and toxic political events to date, with both Democrats and Republicans verbally abusing each other on social media. In France, the 2017 presidential election saw the fall of the major parties (LR and PS) and the rise of the nationalist party led by Marine Le Pen and a newly-born unaffiliated movement created by Emmanuel Macron: La République en Marche, and, in late 2018, the Yellow Vests protests broke out and outlasted even the protest of May 1968. Many more examples could be cited, such as Brexit, Viktor Orban’s erosion of the rule of law in Hungaria, Jair Bolsonaro’s election in Brazil, the Hong Kong protests, and many more. Worldwide, democracies seem to be crumbling: how can we restore and reassert their legitimacy? We will not be so bold as to declare we have found a silver bullet to the rise of authoritarian regimes, but we will nevertheless try and suggest promising ideas.

The Rules of Politics

First of all, if we are to overhaul the building blocks of our democracies, we must gain fundamental understanding of how politics work. Why do some countries take the authoritarian road while other ones become hosts to governments with free elections?

The Rules for Rulers

The power of a king is not to act but to get others to act for him, often through the help of money. In dictatorships, three rules prevail: dictators must get the key supporters - that is, the people who have financial or military power - on their side, and they must control the treasure and buy the key supporters’ loyalty. Then, they have to minimize the number of key supporters, since key supporters needed to gain power are not the same as the ones needed to maintain it.

In democracies, power is fractured and earned with words, not violence. Citizens are divided into blocks which politicians can reward as groups. For instance, farming subsidies have no correlation with how much food a country needs, but instead with how much influence farmers have on elections. That’s why populists sometimes manage to garner substantial support despite being disliked by a large part of the population: they cater to a specific subset of the voters which is receptive to their shenanigans. For instance, Donald Trump’s target is mainly the rural, white and low-educated American population.

The main difference between both cases is that dictators have no need to please the crowds, especially when the nation’s wealth comes from natural resources (minerals, oil…). On the contrary, elected representatives need productivity to increase treasury and therefore to increase the money they can give to their keys, hence they create hospitals, universities… Representatives generally last longer than dictators because their goals are generally more aligned with those of the population. When a dictator is replaced by the people, it is because their keys let the people do so. The people never replace the ruler: the court does. That’s why the following ruler is generally even worse, because they need to keep the keys’ loyalty. In stable democracies, aspiring dictators struggle to gain support because the potential key supporters, more educated, have to weigh the probabilities of making it through the revolt. The more the wealth of a nation comes from the productivity of the citizens, the more the rulers have to redistribute that wealth to the citizens. Democracies typically fall when the treasure becomes empty or when natural resources which dwarf citizen’s productivity are discovered.

Therefore, we will reduce the scope of our reasoning to states which are already democratic, that is most of the Western world. It would be a pipe dream to imagine being able to turn China or Saudi Arabia into a democracy as of today. However, we may reasonably gather ideas which would improve existing democratic systems.

De Mesquita’s Principle

Bruce Bruno de Mesquita offers a very insightful take on politics. According to him, all politicians follow a very basic desire which consists in only two things: to get hold of power and to keep it. A politician is not “good” or “evil” per se: they will make different choices based on the incentives provided by their environment. From this fundamental principle, many other principles can be deduced:

- Corollary 1: what a politician really thinks is irrelevant. What matters to them are the other politicians, lobbies and voters they owe.

- Corollary 2: merit and responsibility are bad predictors of politics.

- Corollary 3: politicians are not stupid. Otherwise, they wouldn’t have won at the game of politics.

- Corollary 4: to be “right” is irrelevant in politics. What matters is to get the support of the population.

- Corollary 5: it is extremely difficult to introduce new ideas in politics because voters and other politicians will most likely not heed them.

- Corollary 6: voters should not vote for ideals or individuals; they should take into account the incentives that will be provided to the different political parties and vote for the political party that will receive the incentives most aligned with their own values.

A very natural question follows from those rules: how do politicians attain power? Through elections. Let us then examine the current ballot systems of Western democracies.

The Ballot Conundrum

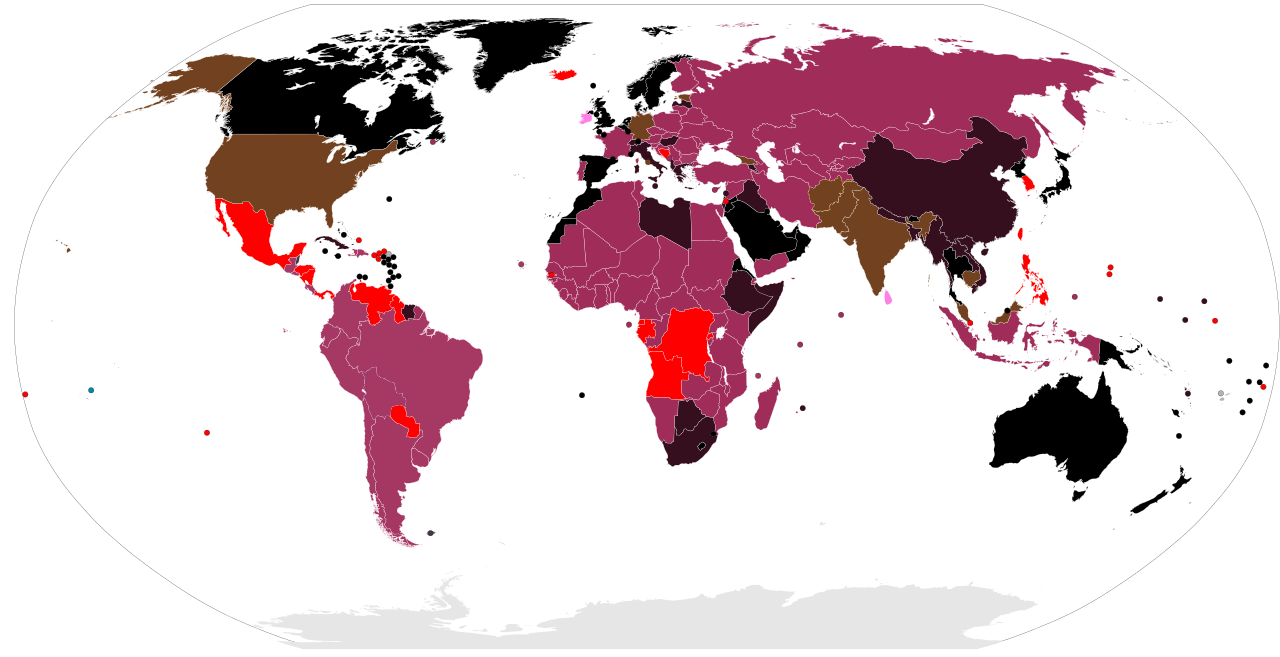

The Current Distribution of Voting Systems

Voting systems can be divided in three main categories:

- Plurality systems are systems in which the candidate(s) with the highest number of votes wins, with no requirement to get a majority of votes, such as the US first-past-the-post ballot.

- Majoritarian systems are systems in which candidates have to receive a majority of the votes to be elected, although in some cases only a plurality is required in the last round of counting if no candidate can achieve a majority, such as instant-runoff voting (Australia) or two-round systems (France).

- Proportional systems are systems in which divisions in an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body. Party-list proportional representation is the single most common electoral system for national legislatures, being used by 80 countries, and involves voters voting for a list of candidates proposed by a party.

The most common system used for presidential elections around the world is the two-round system, being used in 88 countries.

First past the post (FPTP)

Two-round system (TRS)

Instant-runoff voting (IRV)

Election by legislature

Election by electoral college or local legislatures

No direct election

Ballot Properties and Theorems

Unbeknownst to most voters, the single most important factor in election results is, in fact, the choice of the ballot. However, it so happens that two of the most used voting systems - the first-past-the-post and two-round systems - are arguably flawed ballots, at least more so than others. Indeed, they are dependent on irrelevant alternatives, which is an intuitively bad mathematical property, as opposed to independence from irrelevant alternatives which is defined as such: if one candidate (X) would win an election, and if a new candidate (Y) were added to the ballot, then either X or Y would win the election. Independence from irrelevant alternatives is an intuitively reasonable assumption, but both systems do not have that property. A good example of dependence on irrelevant alternatives is illustrated by this example:

After finishing dinner, Sidney Morgenbesser decides to order dessert. The waitress tells him he has two choices: apple pie and blueberry pie. Sidney orders the apple pie. After a few minutes the waitress returns and says that they also have cherry pie at which point Morgenbesser says “In that case I’ll have the blueberry pie.”

They are also exposed to the tactical voting dilemma: voters support another candidate more strongly than their sincere preference in order to prevent an undesirable outcome. This is partly what happened in the 2017 French presidential election: many voters chose either Mr. Macron or Ms. Le Pen during the first round rather than another candidate which had fewer chances to win.

Mathematicians have in fact devised theorems which put strict boundaries on what we can expect from a ballot:

- Arrow’s impossibility theorem: no rank-order electoral system can be designed that always satisfies these three “fairness” criteria:

- If every voter prefers alternative X over alternative Y, then the group prefers X over Y.

- If every voter’s preference between X and Y remains unchanged, then the group’s preference between X and Y will also remain unchanged (even if voters’ preferences between other pairs like X and Z, Y and Z, or Z and W change).

- There is no “dictator”: no single voter possesses the power to always determine the group’s preference.

In summary, Arrow’s theorem states that when voters have three or more distinct alternatives (options), no ranked voting electoral system can convert the ranked preferences of individuals into a community-wide (complete and transitive) ranking.

-

Gibbard-Satterthwaite theorem: for every voting rule, one of the following three things must hold:

- The rule is dictatorial, i.e. there exists a distinguished voter who can choose the winner; or

- The rule limits the possible outcomes to two alternatives only; or

- The rule is susceptible to tactical voting: in certain conditions some voter’s sincere ballot may not defend their opinion best.

-

Gibbard’s 1977 theorem is an extension of the previous theorem when including random strategies. The only voting scheme which satisfies anonymity, unanimity and is strategy-proof is a random dictatorship.

The Randomized Condorcet Method

Although the aforementioned theorems guarantee that a perfect ballot doesn’t exist, it is possible to build a ballot which exhibits better properties than the first-past-the-post and two-round systems. We will here advocate for the randomized Condorcet method, which is based on a simple and intuitive principle. Indeed, Condorcet’s principle is the following: if a candidate is supported by the absolute majority of voters, then he must be elected.

The (non-randomized) Condorcet method elects the candidate that wins a majority of the vote in every head-to-head election against each of the other candidates, that is, a candidate preferred by more voters than any others, whenever there is such a candidate. In practice, an equivalent and simpler implementation of the Condorcet method is the following: each voter ranks the candidates; every ranking is aggregated in a duel graph; and the Condorcet winner can be algorithmically computed if there is one. A glaring problem with this ballot is that there can be no winner, typically when there is a rock-paper-scissors situation. In that case, the elegant solution suggested by the randomized Condorcet method is to elect not a candidate, but a distribution of probability. The winner will then be randomly selected from that distribution. How to elect a distribution? We can generalize Condercet’s principle to define how a distribution wins over another: distribution P wins over Q if on average, a candidate X sampled from P wins in a duel with a candidate Y sampled from Q. We then have to study the graph of duels between distributions. It is a gigantic graph but it has a key property: if there is no equality between candidates, there always exists a unique Condorcet winner in the graph of distribution duels. To be clear, the need to elect a distribution only arises when a deterministic Condorcet winner cannot be found: if there is one, there is no need to randomly select a winner.

The randomized Condorcet voting system is satisfactory because, first, it is based on Condorcet’s principle which is a very intuitive assumption; it has been proven to have the independence of irrelevant alternatives property; and, if there exists a deterministic Condorcet winner, it has been proven not to be vulnerable to tactical voting.

Now that we have detailed why this ballot is a better one than the ones used in Western democracies, a few questions remain: how can people use it best? Since they have to rank candidates, it would be suitable for them to have all the information they need to give preference to the candidates which are most aligned with their own political stances. Navigating in a world marred with omnipresent fake news is no easy task; nevertheless, a technological solution based on AI appears promising.

AI for Enlightened Citizens

In the 2019 Stanford Human-Computer Interaction Seminar, Min Kyung Lee from Carnegie Mellon University introduced WeBuildAI, a participatory framework for algorithmic governance. She observed that AI’s influence over our daily lives has been steadily increasing through social networks, automation, and management among others, and argues that the participation of stakeholders in a framework makes it assessed as more legitimate.

412 Food Rescue, an NGO, asked for an algorithmic framework for automating decisions and improving efficiency. Lee’s team conducted interviews with the stakeholders to determine the most relevant features such as client characteristics, travel distance, and recipient donations. They then pit two methods against each other: machine learning methods and user-created methods. They followed an iterative model building process by successively fine-tuning both methods several times and let users choose the method which best reflected their individual beliefs. They used a collective aggregation with a voting method which used rankings and points. (described in detail in Kahng, Statistical foundations of virtual democracy). The algorithmic models had similar guiding principles but differed in their definitions of efficiency.

As for the results, the experiment increased awareness of the NGO’s internal inconsistencies and led to revising assumptions. Compared to human distributions, the algorithmic distributions decreased average distance, gave priority to poorer areas, and increased perceived fairness and trust towards the organization. They made stakeholders more empathetic towards the organization and better understand the difficulty it faces. There were concerns on other participants’ input quality and an initial doubt whether algorithms can make complex decisions but, eventually, stakeholders were more accepting of it as they understood it better, especially since the algorithm explained to them how they were involved in the overall decision process.

In summary, the goal of the experiment was to design AI agents that would help stakeholders with decision-making: to that end stakeholders themselves played a role in the fine-tuning of their assigned AI agents so that the AI would learn the stakeholders’ preferences. The AI would then compute decisions based on the stakeholders’ input and provide explanations for the results. The latter point is very important: as written above, it increased perceived fairness and trust. The stakeholders would then vote, with the knowledge of the agents’ opinions, to choose the course of action of the NGO.

Although WeBuildAI is only in an embryonary state, it paves the way for a transparent AI framework able to gather political data relative to one’s country and compute rankings based on the users’ preferences while giving detailed explanations for the resulting ranking. This, coupled with a strong voting system such as the randomized Condorcet method, would not only help users make enlightened political choices during elections thanks to an access to factual information, but it would also give strong incentives to politicians to play fair and deter them from trying to divide the population with disinformation. Indeed, their lies would be more easily exposed, and a strong ballot would put them in a disadvantageous position since they would be ranked very low by a large part of the population, unless they managed to gather an absolute majority of votes. From De Mesquita’s principles, since populist strategies would be weakened by such a framework, we can infer that politicians would switch to a strategy based on more transparency and honesty. At least, that is what we believe.

As a conclusion for this essay, let us imagine a future where planets align and democracy rises from its ashes and is born anew.

Conclusion - The Democratic Phoenix

November 3rd 2020

November 8th 2020

November 9th 2020

November 23rd 2020

November 26th 2020

December 4th 2020

December 6th 2020

December 9th 2020

January 15th 2021

February 22nd 2021

February 26th 2021

March 7th 2021

March 8th 2021

March 9th 2021

April 14th 2021

May 5th 2021

June 25th 2021

October 24th 2021

November 6th 2021

November 8th 2025